Large data

Overview

Teaching: 30 min

Exercises: 30 minQuestions

How do I work with multiple CMIP files that won’t fit in memory?

Objectives

Inspect netCDF chunking.

Import the dask library and start a client with parallel workers.

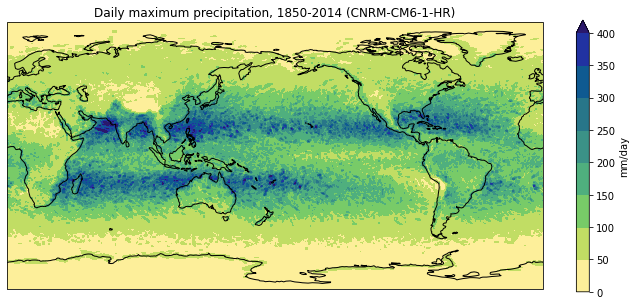

Calculate and plot the maximum daily precipitation for a high resolution model.

So far we’ve been working with small, individual data files that can be comfortably read into memory on a modern laptop. What if we wanted to process a larger dataset that consists of many files and/or much larger file sizes? For instance, let’s say the next step in our global precipitation analysis is to plot the daily maximum precipitation over the 1850-2014 period for the high resolution CNRM-CM6-1-HR model.

Data download

We’ll look at CMIP6 data. Since the files are large (48GB), it is optional for learners to download the dataset. However, should the learners wish to proceed and download the data, this can be done in different ways.

On NeSI, we’ve downloaded the data for you and stored them under

/nesi/nobackup/icshmo_python_aos/data.If you wish to download the data yourself, you can use the Synda software. For NIWA users, the following commands will search the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) catalogue, find out the size of the dataset and asynchronously download the data on NeSI’s platforms:

$ source /nesi/project/niwa02916/synda_env.sh $ synda search source_id=CNRM-CM6-1-HR variable=pr table_id=day experiment_id=historical $ synda stat CMIP6.CMIP.CNRM-CERFACS.CNRM-CM6-1-HR.historical.r1i1p1f2.day.pr.gr.v20191021 $ synda install CMIP6.CMIP.CNRM-CERFACS.CNRM-CM6-1-HR.historical.r1i1p1f2.day.pr.gr.v20191021You can then find the files under

$ST_HOME/data/CMIP6/CMIP/CNRM-CERFACS/CNRM-CM6-1-HR/historical/r1i1p1f2/day/pr/gr/v20191021. Alternatively, you can copy the data from/nesi/nobackup/icshmo_python_aos/data/*.ncon NeSI’s HPC:

Once the data are copied into the data/ directory,

we can inspect the dataset and see that the daily maximum precipitation data

for the 1850-2014 period has been broken up into 25-year chunks and

spread across seven netCDF files,

most of which are 6.7 GB in size.

$ ls -lh data/pr*.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 6.7G 26 Jan 12:09 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_18500101-18741231.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 6.7G 26 Jan 13:14 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_18750101-18991231.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 6.7G 26 Jan 14:17 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19000101-19241231.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 6.7G 26 Jan 15:20 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19250101-19491231.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 6.7G 26 Jan 16:24 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19500101-19741231.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 6.7G 26 Jan 17:27 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19750101-19991231.nc

-rw-r----- 1 irving staff 4.0G 26 Jan 18:05 pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_20000101-20141231.nc

In order to work with these files,

we can use xarray to open a “multifile” dataset as though it were a single file.

Our first step is to open a new Jupyter notebook and

import a library with a rather unfortunate name.

import glob

The glob library contains a single function, also called glob,

that finds files whose names match a pattern.

We provide those patterns as strings:

the character * matches zero or more characters,

while ? matches any one character,

just like at the Unix shell.

pr_files = glob.glob('data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_*.nc')

pr_files.sort()

print(pr_files)

['/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_18500101-18741231.nc',

'/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_18750101-18991231.nc',

'/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19000101-19241231.nc',

'/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19250101-19491231.nc',

'/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19500101-19741231.nc',

'/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_19750101-19991231.nc',

'/Users/irving/Desktop/data-carpentry/data/pr_day_CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2_gr_20000101-20141231.nc']

Recall that when we first open data in xarray

it simply (“lazily”) loads the metadata associated with the data

and shows summary information about the contents of the dataset

(i.e. it doesn’t read the actual data into memory).

This may take a little time for a large multifile dataset.

import xarray as xr

dset = xr.open_mfdataset(pr_files, chunks={'time': '500MB'})

print(dset)

<xarray.Dataset>

Dimensions: (axis_nbounds: 2, lat: 360, lon: 720, time: 60265)

Coordinates:

* lat (lat) float64 -89.62 -89.12 -88.62 -88.13 ... 88.62 89.12 89.62

* lon (lon) float64 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 ... 358.0 358.5 359.0 359.5

* time (time) datetime64[ns] 1850-01-01T12:00:00 ... 2014-12-31T12:...

Dimensions without coordinates: axis_nbounds

Data variables:

time_bounds (time, axis_nbounds) datetime64[ns] dask.array<chunksize=(9131, 2), meta=np.ndarray>

pr (time, lat, lon) float32 dask.array<chunksize=(397, 360, 720), meta=np.ndarray>

Attributes:

Conventions: CF-1.7 CMIP-6.2

creation_date: 2019-05-23T12:33:53Z

description: CMIP6 historical

title: CNRM-CM6-1-HR model output prepared for CMIP6 and...

activity_id: CMIP

contact: contact.cmip@meteo.fr

data_specs_version: 01.00.21

dr2xml_version: 1.16

experiment_id: historical

experiment: all-forcing simulation of the recent past

external_variables: areacella

forcing_index: 2

frequency: day

further_info_url: https://furtherinfo.es-doc.org/CMIP6.CNRM-CERFACS...

grid: data regridded to a 359 gaussian grid (360x720 la...

grid_label: gr

nominal_resolution: 50 km

initialization_index: 1

institution_id: CNRM-CERFACS

institution: CNRM (Centre National de Recherches Meteorologiqu...

license: CMIP6 model data produced by CNRM-CERFACS is lice...

mip_era: CMIP6

parent_experiment_id: p i C o n t r o l

parent_mip_era: CMIP6

parent_activity_id: C M I P

parent_source_id: CNRM-CM6-1-HR

parent_time_units: days since 1850-01-01 00:00:00

parent_variant_label: r1i1p1f2

branch_method: standard

branch_time_in_parent: 0.0

branch_time_in_child: 0.0

physics_index: 1

product: model-output

realization_index: 1

realm: atmos

references: http://www.umr-cnrm.fr/cmip6/references

source: CNRM-CM6-1-HR (2017): aerosol: prescribed monthl...

source_id: CNRM-CM6-1-HR

source_type: AOGCM

sub_experiment_id: none

sub_experiment: none

table_id: day

variable_id: pr

variant_label: r1i1p1f2

EXPID: CNRM-CM6-1-HR_historical_r1i1p1f2

CMIP6_CV_version: cv=6.2.3.0-7-g2019642

dr2xml_md5sum: 45d4369d889ddfb8149d771d8625e9ec

xios_commit: 1442-shuffle

nemo_gelato_commit: 84a9e3f161dade7_8250e198106a168

arpege_minor_version: 6.3.3

history: none

tracking_id: hdl:21.14100/223fa794-73fe-4bb5-9209-8ff910f7dc40

We can see that our dset object is an xarray.Dataset,

but notice now that each variable has type dask.array

with a chunksize attribute.

Dask will access the data chunk-by-chunk (rather than all at once),

which is fortunate because at 48GB the full size of our dataset

is much larger than the available RAM on most laptops.

Dask can also distribute chunks across multiple cores if we ask it to

(i.e. parallel processing).

So how big should our chunks be? As a general rule they need to be small enough to fit comfortably in memory (because multiple chunks can be in memory at once), but large enough to avoid the time cost associated with asking Dask to manage/schedule lots of little chunks. The Dask documentation suggests that chunk sizes between 10MB-1GB are common, so we’ve set the chunk size to 500MB in this example. Since our netCDF files are chunked by time, we’ve specified that the 500MB Dask chunks should also be along that axis. Performance would suffer dramatically if our Dask chunks weren’t aligned with our netCDF chunks.

We can have the Jupyter notebook display the size and shape of our chunks, just to make sure they are indeed 500MB.

dset['pr'].data

Array Chunk

Bytes 62.48 GB 499.74 MB

Shape (60265, 360, 720) (482, 360, 720)

Count 307 Tasks 150 Chunks

Type float32 numpy.ndarray

Now that we understand the chunking information contained in the metadata, let’s go ahead and calculate the daily maximum precipitation.

pr_max = dset['pr'].max('time', keep_attrs=True)

print(pr_max)

<xarray.DataArray 'pr' (lat: 360, lon: 720)>

dask.array<nanmax-aggregate, shape=(360, 720), dtype=float32, chunksize=(360, 720), chunktype=numpy.ndarray>

Coordinates:

* lat (lat) float64 -89.62 -89.12 -88.62 -88.13 ... 88.62 89.12 89.62

* lon (lon) float64 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 ... 357.5 358.0 358.5 359.0 359.5

Attributes:

long_name: Precipitation

units: kg m-2 s-1

online_operation: average

cell_methods: area: time: mean

interval_operation: 900 s

interval_write: 1 d

standard_name: precipitation_flux

description: at surface; includes both liquid and solid phases fr...

history: none

cell_measures: area: areacella

It seems like the calculation happened instataneously,

but it’s actually just another “lazy” feature of xarray.

It’s showing us what the output of the calculation would look like (i.e. a 360 by 720 array),

but xarray won’t actually do the computation

until the data is needed (e.g. to create a plot or write to a netCDF file).

To force xarray to do the computation

we can use .load() with the %%time Jupyter notebook command

to record how long it takes:

%%time

pr_max.load()

CPU times: user 4min 1s, sys: 54.2 s, total: 4min 55s

Wall time: 3min 44s

By processing the data chunk-by-chunk,

we’ve avoided the memory error we would have generated

had we tried to handle the whole dataset at once.

A completion time of 3 minutes and 44 seconds isn’t too bad,

but that was only using one core.

We can try and speed things up by using a dask “client”

to run the calculation in parallel across multiple cores:

from dask.distributed import Client

client = Client()

client

Client Cluster

Scheduler: tcp://127.0.0.1:59152 Workers: 4

Dashboard: http://127.0.0.1:8787/status Cores: 4

Memory: 17.18 GB

(Click on the dashboard link to watch what’s happening on each core.)

Now rerun your computation with the distributed clients running:

%%time

pr_max = dset['pr'].max('time', keep_attrs=True)

pr_max.load()

CPU times: user 10.2 s, sys: 1.12 s, total: 11.3 s

Wall time: 2min 33s

By distributing the calculation across all four cores the processing time has dropped to 2 minutes and 33 seconds. It’s faster than, but not a quarter of, the original 3 minutes and 44 seconds because there’s a time cost associated with setting up and coordinating jobs across all the cores.

Now that we’ve computed the daily maximum precipitation, we can go ahead and plot it:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import cartopy.crs as ccrs

import numpy as np

import cmocean

pr_max.data = pr_max.data * 86400

pr_max.attrs['units'] = 'mm/day'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=[12,5])

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection=ccrs.PlateCarree(central_longitude=180))

pr_max.plot.contourf(ax=ax,

levels=np.arange(0, 450, 50),

extend='max',

transform=ccrs.PlateCarree(),

cbar_kwargs={'label': pr_max.units},

cmap=cmocean.cm.haline_r)

ax.coastlines()

model = dset.attrs['source_id']

title = f'Daily maximum precipitation, 1850-2014 ({model})'

plt.title(title)

plt.show()

Writing your own Dask-aware functions

So far leveraging Dask for our large data computations has been relatively simple, because almost all of

xarray’s built-in operations (likemax) work on Dask arrays.If we wanted to chunk and parallelise code involving operations that aren’t built into

xarray(e.g. an interpolation routine from the SciPy library) we’d first need to use theapply_ufuncormap_blocksfunction to make those operations “Dask-aware”. The xarray tutorial from SciPy 2020 explains how to do this.

Parallel computing on NeSI

Sometimes, the computing power on your laptop or desktop is not enough. At this point you may want to run your analysis on a supercomputer. The following script will compute the global maximum of precipitation across all times, latitudes and longitudes.

import glob import xarray as xr import dask import time if __name__ == '__main__': tic = time.time() with dask.config.set(scheduler='processes'): pr_files = glob.glob('/nesi/nobackup/icshmo_python_aos/data/*.nc') ds = xr.open_mfdataset(pr_files, chunks={'time': 100}) prmax_all = ds['pr'].max(('time', 'lat', 'lon'), keep_attrs=True) prmax_all.load() print(prmax_all.data) toc = time.time() print(f'max: {prmax_all.values} took {toc - tic:.2f} sec')You can submit the script with

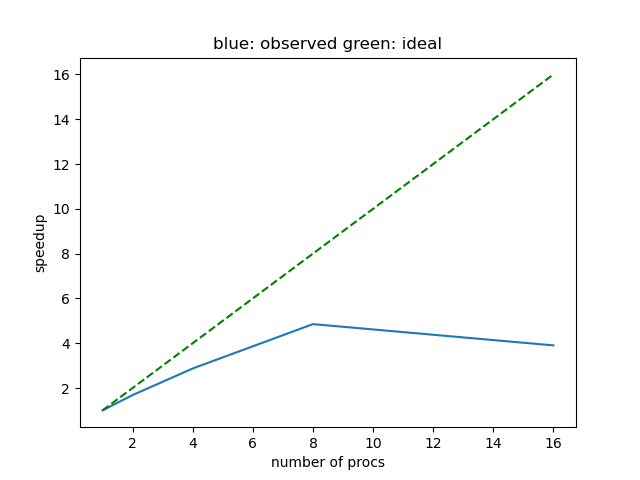

$ srun --cpus-per-task=10 --mem=3gb --ntasks=1 --hint=nomultithread python historical_max_precip.pyHere, we use 10 processes to share the workload. if you vary the number of processes you will likely observe that the improvement in execution time plateaus, and often even decreases beyond a number of processes. This is shown in the plot below where we can see that the maximum performance is achieved using 8 processes.

Also note that the parallel efficiency, the ratio between the observed (blue solid line) and the ideal speedup (green dashed line) is often less than perfect (less than 100 percent). This can be due to some tasks taking less time than others, which causes some processes to wait for others to finish. Another reason for imperfect parallel scalability is that more processes demand more data to be instantiated and copied between processes, which can also slow down execution.

Ultimately, the speedup will also depend on the size of your data, more scalability can be expected with larger datasets, and on chunking as well as other factors. Try to change the chunking and rerun the problem to see how the parallel scalability changes.

Alternatives to Dask

While

daskcan be a good option for working with large data, it’s not always the best choice. For instance, in this lesson we’ve talked about the time cost associated with setting up and coordinating jobs across multiple cores, and the fact that it can take a bit of time and effort to make a function Dask-aware.What other options/tactics do you have when working with a large, multi-file dataset? What are the pros and cons of these options?

Solution

Other options include writing a loop to process each netCDF file one at a time or a series of sub-regions one at a time.

By breaking the data processing down like this you might avoid the need to make your function/s Dask-aware. If the loop only involves tens (as opposed to hundreds) files/regions, the loop might also not be too slow. However, using Dask is neater and more scalable, because the code you write looks essentially the same regardless of whether you’re running the code on a powerful supercomputer or a personal laptop.

Find out what you’re working with

Setup a Dask client in your Jupyter notebook. How many cores do you have available and how much memory?

Solution

Run the following two commands in your notebook to setup the client and then type

clientto view the display of information:from dask.distributed import Client client = Client() client

Applying this to your own work

In your own research, are there any data processing tasks that could benefit from chunking and/or parallelisation? If so, how would you implement it? What size would your chunks be and along what axis? Are all the operations involved already Dask-aware?

Key Points

Libraries such as dask and xarray can make loading, processing and visualising netCDF data much easier.

Dask can speed up processing through parallelism but care may be needed particularly with data chunking.